Do not miss Audubon’s Aviary: Part I of the Complete Flock at the New York Historical Society. Running from Friday, March 8 through Sunday, May 19, this is the first installment of a three-part exhibition that will stretch over three years and feature all of John James Audubon’s 474 original watercolors, along with nearly as many study pieces. These paintings, which the NYHS acquired 150 years ago this spring, were the basis for the hand-colored engravings that made up the double-elephant folio Birds of America.

Great Egret: New York Historical Society

Great Egret: New York Historical Society

“Once-in-a-lifetime” is not an overstatement when describing this exhibition. Although the NYHS has shown these paintings many times, and in many different groupings, never before has it displayed the entire collection as it is doing now. Even more exciting, curator Roberta J. M. Olson decided to organize the birds in the order they were printed and delivered to subscribers. That inspired organization allows visitors a better understanding of Audubon’s business sense – and showmanship. Although Audubon’s subscribers agreed to buy the entire set of prints, which he produced in groups (or fascicles) over twelve years, they could cancel at any time – and some did. Audubon realized that he needed to keep his subscribers engaged and eager for the next fascicle, so each delivery included one large print, one medium, and three small, a mixture of the more spectacular birds along with the more ordinary.

And, that’s how the birds are displayed in the NYHS’s second floor galleries, a space transformed into a painted aviary: birds in flight, birds at rest, birds nesting, birds feeding – birds everywhere. Complementing the paintings are media installations (heard via hand-held devices) that draw correlations between the birds in art and in nature. Down the hall, the history-minded can find some pieces of Auduboniana in a small, comfortable room. Among the documents is a letter Lucy Audubon wrote to Frederic De Peyster, the president of the NYHS in 1863, when she was negotiating the sale of her husband’s paintings and accompanying studies. That letter is a timely reminder of Lucy Audubon’s role in ensuring that her husband’s visual legacy would be preserved and maintained.

Lucy Audubon, Businesswoman

History has treated Lucy well. Audubon biographies and surveys of his work routinely portray her as a selfless helpmate whose sacrifices and industry enabled the naturalist to pursue the labors that resulted in his masterpiece, but Lucy Audubon was far more complex than that – and for the most part far more self-absorbed. Her negotiations to sell her husband’s paintings to the NYHS, recorded in correspondence in the Society’s library and in the New York Public Library, reveal an extremely clever and resourceful businesswoman. They also reveal a woman who was determined to ensure her financial independence even if that meant shading the truth or disparaging members of her family. Far from being sentimental about the paintings, or as she called them the “drawings,” Lucy clearly considered her husband’s art as her rightful inheritance, a commodity to be sold to the highest bidder.

Lucy opened her negotiations with the NYHS in December 1862 when she contacted the librarian George Henry Moore, to test his interest in the drawings. After a sentimental salvo about her husband’s wishes and a well-placed hint that she had other potential buyers, she named her price: $5,000 (approximately$115,000 in today’s buying power). She also offered to sell “the coppers” (the copper plates the engraver used to create the prints) and informed Moore that if she could not find a buyer, she would sell them “by weight as old Copper,” that is, they would be melted down. While that seems an ignominious fate for the plates used to create her husband’s masterpiece, Lucy had learned that the plates deteriorated over time, so they would eventually be useless. In the midst of her letter, Lucy referenced a theme she would repeat in various forms throughout the negotiations: the proceeds from the sale would “relieve the orphan and widow,” a somewhat deceptive phrase that we’ll investigate in more detail further on.

Audubon’s Aviary: The Original Watercolors for the Birds of America

Audubon’s Aviary: The Original Watercolors for the Birds of America

Written by Roberta J.M. Olson with a contribution by Marjorie Shelley

Lucy had attempted to sell her husband’s drawings before. In 1854, a few years after Audubon’s death, the New York Times reported on page one that Edward Everett, a Senator from Massachusetts, “presented the Memorial of the widow of Audubon, praying that Congress would purchase the original drawings by her husband of The Birds of America.” That attempt failed. Perhaps Lucy’s sons Victor and John Woodhouse prevailed upon their mother to reconsider, because over the next decade, she does not appear to have made further attempts to sell either the drawings or the coppers. However, after Victor died in 1860 and John Woodhouse in February 1862, Lucy again began seeking a buyer in earnest, and this time, she made her motives quite plain in a letter to her friend and legal advisor, George Burgess: “I only want the mortgage paid off.”

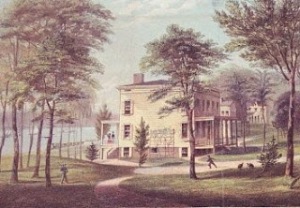

The mortgage in question was an obligation of $20,000 on the house Audubon had built in 1841 and deeded to Lucy, along with the 14-acre farm, Minnie’s Land. Lucy hadn’t lived in her house since about 1853 when Victor and John W. had built houses for their families adjacent to the original Audubon house. Instead, she leased her house and lived six months of the year with one son and then the next six months with the other. At the same time, she was collecting rent from another house she owned, this one in the north-west corner of the farm, just north of her younger son’s home. Despite that solid income, Lucy was constantly worried about supporting herself and her family; those worries only increased after John W.’s death in 1862, which is when she once again began exploring the possibility of selling the drawings and coppers.

Lucy Audubon, Breadwinner

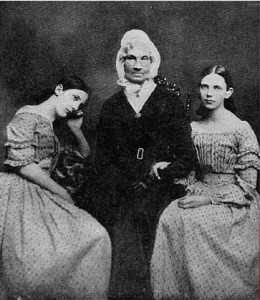

Lucy Audubon with her granddaughters Lulu (left) and Hattie (right)

Lucy Audubon with her granddaughters Lulu (left) and Hattie (right)

Before proceeding further with the narrative, we should stop a moment to consider what Lucy meant when she referred to “her family,” as that definition is important for understanding her correspondence related to the drawings. John James and Lucy Audubon had two daughters who died in infancy and two sons who lived to adulthood. The sons each married twice (both of their first wives died of consumption while still in their 20s), and between them had 16 children, 14 of whom survived childhood. Among her grandchildren, Lucy Audubon had a very special relationship with the two eldest, Lucy (Lulu) and Harriet (Hattie), who were John W.’s daughters by his first wife. When their mother died, Lulu was a toddler and Hattie an infant. Claiming that it was her daughter-in-law’s last wish, Lucy raised the two girls as her own children, substituting them for the two daughters she had lost decades earlier.

While Audubon was alive, the entire family had lived as one unit in the original house, but after his death in 1851, the family began splitting into three distinct units. That split increased when Victor and John built their own houses and then became even more pronounced after John W. died and Lucy focused increasingly on the welfare of her family unit: Lulu, Hattie, and herself. When Lulu married Delancy Williams in 1858 and moved to her husband’s farm, Lucy’s family unit shrank to two. From then on, Lucy (the widow) and Hattie (the orphan) were a modern-day Naomi and Ruth; whithersoever Lucy went, Hattie followed. While both of Hattie’s parents (John W. and his first wife Maria) were indeed dead, describing her as an orphan is a bit misleading, given that in 1863, while the negotiations with the NYHS were ongoing, she was 24 years old and had been earning an income as a music teacher for several years as well as earning additional income playing the organ at the Church of the Intercession. She was – and remained into her 90s – a very independent woman, much like her grandmother.

Between 1851 and 1854, Lucy and her sons had sold the majority of Minnie’s Land. All that remained for the Audubons were the two houses where Victor and John W. lived, the two houses Lucy owned and was leasing, a rental house that belonged to Victor and his wife Georgianna, and the lots accompanying each of those houses. The transformed farm, now a rural suburban enclave of about a dozen villas, earned a new name: Audubon Park. Although Lucy would claim during her negotiations with the NYHS that she had given her property to her sons “to pay debts compiled by them in unsuccessful businesses” and so that they could build houses and raise money through mortgages, the City Register tells a different story. All of the transfers between Lucy and her sons had dollar values attached; Victor and John W. paid their mother market value for the parcels. Even more distressing is reading correspondence between Victor and John W. (while Victor was on the road selling subscriptions to the Quadrupeds of America) and realizing that their objective with these business deals was raising a substantial sum of money they could invest to provide Lucy with a lifetime annuity.

One other item that Lucy mentioned in her negotiations bears elucidation: her school. George Bird Grinnell, as well as others in the generations following Lucy Audubon, passed along the story that in the difficult years following Audubon’s death, Lucy Audubon ran a school and used the proceeds to support her family. This myth has been repeated as fact in numerous accounts, but under a bit of scrutiny, doesn’t pass the test of logic – unless we understand it within Lucy’s definition of family. Numerous references in the Audubon correspondence from the 1840s and ’50s confirm that Lucy ran a school for the purpose of educating her grandchildren, who made up the largest number of her students. The others, whose parents paid nominal fees of $5.00 to $10.00 per pupil per quarter, accounted for only a few of the students in Lucy’s classroom. She could not possibly have earned sufficient income from those few pupils to support the large Audubon family (plus the servants she insisted on having) for a month, much less sustain them over several years. And, even if she had charged her sons to teach her grandchildren, what would have been the sense of then using that money to support her sons and their families?

Minnie’s Land: Lucy Audubon’s house foreground Victor’s and John W’s. houses in distance

Minnie’s Land: Lucy Audubon’s house foreground Victor’s and John W’s. houses in distance

Here again, we must return to Lucy’s definition of family. As she explained to Mr. McPeters, who duly reported to DePeyster (February 24, 1863), “For her own support, consequently Mrs. Audubon was obliged to undertake the teaching of some of the children of the vicinity, assisted by an orphan Grand daughter.” What was true in 1863 had also been true in the 1850s; the income from the school supported Lucy, Lulu (until she was married), and Hattie. Further, although Lucy told McPeters that she ceased teaching because “her strength entirely gave way,” she had told Burgess the previous March that despite trying, she had not been able to get any scholars.

Lucy Audubon, Negotiator

By 1862, when John W. died, Lucy’s saleable assets had dwindled significantly. Even so, in March, she replied to a letter George Burgess had sent her about writing a will. Her first concern was Hattie, her second was Lulu, and then, whatever might be left could go to her other 12 grandchildren. (The “lot and well” in the letter refer to the original Audubon house, though in 1862, Lucy also owned a small lot west of present-day Broadway and the spring that originated there. She would sell that parcel along with the house and land, in 1864.) When Lucy did die, more than a decade later, she left her entire estate, much diminished, to Hattie.

Tufted Titmouse: New York Historical Society

Tufted Titmouse: New York Historical Society

I do not know what I can say about a will when I know not if I shall have anything to leave, but under existing circumstances I think if I leave all personal property, except Books and Pictures, to Harriet, along with the “lot and Well”, the Books and pictures to be divided between the two Sisters Lucy and Harriet. Then such an amount out of what I may have; as my Executors shall deem necessary to make Harriet quite comfortable, if such there be, and whatever there may be left after that; to be divided equally amongst the other Grand children as may be living at the time of dividing my property, be it what it may.

In April 1862, when Lucy began corresponding with George Burgess about selling the copper plates, she was both concerned and indignant because “Mrs. John [John W.’s widow Caroline] says I have no right to them.” In June, she considered writing her remaining contacts in England to inquire about interest in the paintings there and by July, she was considering selling the drawings for $3.00 a piece, which would have yielded only $1,200 ($27,700). In November 1862, Lucy sold William Wheelock the house he had been leasing on a yearly basis for $13,000 ($300,000), seemingly a small fortune, but not enough to assure Lucy that she and Hattie were financially independent. What seemed to bother her even more than her debts was the interest on the mortgage, because it was money she was paying without any visible return.

By December, the negotiations with the NYHS were in full swing and Lucy was updating Burgess on her progress, telling both him and Frederic DePeyster that the British Museum, the King of Portugal, the Prince of Wales, and “friends in Philadelphia” were all interested in purchasing the paintings. While this was not a complete bluff, she may have been exaggerating (or imagining) the interest, since she ultimately did not sell to any of them and never mentions concrete offers.

Of all the letters in the series, the most revealing is the one “Mr. McPeters” wrote to Frederic De Peyster on February 24, 1863, after an interview with Lucy Audubon. In it, McPeters reports Lucy’s claims about her sons unsuccessful businesses, her school, her financial “embarrassments,” and her supposed generosity. That generosity is not confirmed in any other sources, including Lucy’s own letters or the public record, which record that her sons paid her for every parcel they received in Minnie’s Land. The numbers McPeters quotes in the letter are interesting and suggest Lucy was fudging a bit to make her condition seem direr than it was. The total indebtedness she reports is a $20,000 ($370,000) mortgage on her remaining property. Lucy then reported that “by parting with one piece of property” she had reduced her indebtedness to $12,000. When Lucy she sold her house and land to Jesse Benedict in 1864, she received $24,000 ($354,000 – again note the fall in the value of the dollar) and immediately paid $12,000 for the outstanding mortgage, so that sum is accurate. What doesn’t calculate is that in November, she had sold her smaller rental house and the land around it to William Wheelock for $13,000. If she had reduced her $20,000 debt to $12,000, $5,000 is unaccounted for. Granted, she may have used it to repay old debts or taxes, but it might as easily have gone into Lucy’s nest egg. Coincidentally, $5,000 was the amount Lucy had originally named as her price for the drawings.

By April, Lucy was quite frustrated with the lagging negotiations and seeming lack of interest from the NYHS. She wrote Burgess on the 9th that her view of the society was very much in line with his – the suggestion being that neither of them thought highly of it. On the 10th, when she wrote to DePeyster, she switched from her “widow and orphan routine” to irony, “It is somewhat singular that my enthusiastic husband struggled to have his labours published in his Country and couldn’t; and I have struggled to sell his forty years labour and cannot.” In the same letter she strongly hinted that she was packing the paintings to send to England, which being the practical individual she was, she probably would not have done without a firm offer and at least a down payment. Her ploy worked, however, and on the 12th, she wrote to Burgess that Shepherd Knapp, a neighbor just north of Audubon Park, had visited the previous evening to tell her that a committee of 15 “Gentlemen of the Historical Society” had joined “to try and raise the money” to buy the paintings. Soon, a circular appeared for just that purpose. Among the signers were Knapp and Daniel F. Tiemann, former mayor of the city, state assemblyman, and long-time friend of the Audubon family. With the circular, these gentlemen signified their intention of raising $4,000 ($74,000) to purchase Audubon’s drawings.

A couple of weeks later, when the funds had not materialized, Mr. McPeters visited Lucy again, telling her that the NYHS would be happy to buy the paintings, but needed more time to raise the funds. Lucy wrote DePeyster and complained that she was surprised by the delay given that wealth was so “abundant” in New York. She followed that sentiment with a lament that during the months she had been negotiating with the NYHS, she could have been liberated from her “pecuniary embarrassment and England in possession of the Drawings.” Lucy may have shot herself in the foot with that remark. DePeyster probably realized that if anyone in England had really made a firm offer for the drawings, Lucy would have sent them long since and he would have relieved of her tedious letters.

Whether DePeyster was trying his own bargaining tactics or whether he was conveying fact, when he reported to Lucy that the NYHS could only raise $2,000 on subscription ($37,000; due to the falling value of the dollar during the Civil War, if Lucy had sold the painting for this amount a year earlier, the buying power would have been $46,000), she accepted the offer and surrendered the drawings – all of them, the paintings and the studies. (See comments for discussion about the actual sales price.) Before DePeyster could breathe a sigh of relief that the deal was closed, Lucy was writing to him again, once more offering the coppers. With no positive response form DePeyster on the coppers, she offered the Ornithological Biographies, which were lying in a barn up in Audubon Park, molding. They had originally sold for a guinea each, but with booksellers in England ignoring her letters, she offered them to the Society for a dollar a volume. DePeyster did not pursue that sale either and with that letter, their correspondence ended.

The Lucy Audubon who inhabits the correspondence cited here is quite a different individual from the Lucy Audubon portrayed in Audubon biographies and histories. The self-sacrificing helpmate of the latter is hard to reconcile with the determined and often querulous woman in the former. While the negotiating skills she displays in these letters is admirable, her tone can be irritating and her self-image as the martyred mother, downright annoying. Ultimately, however, she knew what she wanted to accomplish, and like her husband, she understood the value of playing a role. Whichever of these personae is the real Lucy Audubon (and most probably, she was a combination of all ) and whatever her ultimate reasons for selling her husband’s paintings to the New York Historical Society, she deserves the thanks of succeeding generations for conveying her husband’s work to an institution that has cared for it, preserved it, and made it available to the public for 150 years.

Excerpts from the Correspondence

These excerpts from Lucy Audubon’s correspondence with George Burgess and Frederic DePeyster during her negotiations to sell her husband’s artwork to the NYHS illustrate her negotiating skills as well as her determination and willingness to spin the story to her advantage. Notations in brackets [ ] are explanatory, not original to the text.

(All correspondence with George Burgess is in the manuscript collection of the New York Public Library: George Burgess papers; all correspondence with the NYHS is in the New York Historical Library manuscript collection, Audubon folder.)

Lucy Audubon to George Burgess, April 28, 1862

…Now I want your opinion about some hundred plates (more or less) I mean as to what I must do with them they were engraved in London long before my Sons took any part in that first work and I thought them mine. Mrs. John [Lucy’s daughter-in-law Caroline Hall Audubon, widow of John W. Audubon] says Mr. Lockwood [of the publishing company Roe Lockwood] told her he had some hundreds of them and that if all these were added to them he might make out a volume of the first large work “Birds of America” therefore Mrs. John says I have no right to them but ought to send them immediately to Lockwood. I said I should ask you before I did it for I do not see the advantage of so doing…

Lucy Audubon to George Burgess, June 26, 1862

…I have been thinking that Mr. Bean might know of someone who would like to purchase the Coppers even for less than their value would help me to pay my debts. A little while before Johns death he received a letter from some Sir Henry something Curator of the British Museum in London, saying “if” the Widow of J. J. Audubon would send over the original drawings of Mr. Audubon he would sell them for the Widows benefit better he thought than they would sell in America. All our old and true friends amongst the aristocracy are gone, but there are one or two Persons who were friends all the time we were in England, that I could write to, if you think it a plan likely to succeed. I will not only write to the Curator but to Honable Thomas Liddle who always took great interest in us, and Sir Wm Wood. And if you think it worth while I will have them packed here and a list made of the plates. I perhaps appear impatient and restless to you, but Mr. Burgess it is hard to work all day every day and at the end of a quarter find just enough to pay our Board. I see no way of paying the debts, nor have I even the means of going anywhere.

Lucy Audubon to George Burgess, July 31, 1862

…I still hope to get something worth having from the drawings and Coppers … I will be patient certainly but I cannot be quite passive (?), I must be trying to help myself out of this great indebtedness … I think Mr. Bien will help me about the drawings and coppers. The drawings 430 at three dollars each all round would be twelve hundred and 90.

Lucy Audubon to George Burgess, November 25, 1862

… I mentioned the affair of gradual payments for the Drawings because the plan might suit another. The person in question is just beginning the world and I found his friends had no intention that he should so gratify himself, but I said to Mr. Peters of Bloomingdale that I would take 4,000 dollars in cash at once, or 5 or 6,000 in sums annually, of one thousand or every six months. I do not think, these times that they will be easily sold, and I want to get on to the end of this ruinous Interest business …

Lucy Audubon to George Burgess, December 3, 1862

… I have seen four of the leading Professors of the Scientific Academies and they have no funds for Drawings I have seen also the first engravers and Publishers and they advise me as did Mr. Havell [Audubon’s British engraver who had emigrated to the United States in 1840] to sell the Coppers as old Copper because they will injure by time as engravings and Lithography has taken the place of Metal. Mr. George Childs who is first here in that line says he will put his own name at the head of a subscription list to obtain 5,000 for the Drawings to place them as soon as he can and from the character he has I hope, but in the meantime he said I might sell if I could …

Lucy Audubon to George Henry Moore, December 1862

“…it was always the wish of Mr. Audubon that his forty years labor should remain in his country, therefore I give the preference to this society over my request to send them to the British Museum…should your Society purchase them, you will possess the only work of the kind in the world and relieve the orphan and widow. I have friends in Philadelphia who are joining their efforts to possess(?) these drawings, but I left them with the liberty to sell them, if I could before the six weeks they spoke of expired. The price of them is 5,000$. Less than that would be too great a sacrifice. I have also the Copper plates…I shall sell by weight as old Copper, if not otherwise valued.”

Lucy Audubon to George Burgess, December 12, 1862

… Mr. Peters writes me … I will copy what he says truly “I received a note today from Mr. Moore of the Historical Library. He agrees with me that you had better accept any positive offer for them than wait the action of of (sic) a slow corporate body. The Historical Society has not acted, & it will go now a week certainly before they come to any decision. If you can get $4,000 in semiannual payments I would certainly advise you to accept.” … Now if they would pay me one thousand down and the other three each following six months it might help me to clear the mortgage. And the sale of the coppers even by weight … Excuse my writing on half sheets of paper I have no other. The date of Mr. Peter’s letter is Dec. 8 next Monday will be a week. Pray do for me as you think best, I know it is far below their value as works of art, but art is at a very low ebb just now. Mr. Wheelock [Lucy Audubon’s tenant in Audubon Park, who eventually bought the house he leased] knows Mr. Moore intimably (sic). I do hope to be able to pay you and all others soon.

Lucy Audubon to George Burgess, December 18, 1862

… I sent you word the Historical Society would meet last Monday, I think from the tenor of Mr. Peters letter they would expect me to acquiesce to their terms or not, Mr. W[heelock]thought they would write to me again but they have not, and I venture my poor judgement by saying to you that one thousand dollars down with four from Mrs. John and at least two thousand or even on from the Coppers would make six then the other three thousand every six months would make nine, and the rent of the old house and the lot would make another thousand & the coppers ought to bring more. I am willing to make great sacrifices to pay these debts …

“Mr. McPeters” to Frederic De Peyster, February 24, 1863 (written after an interview with Lucy Audubon)

…Her present embarrassments have arisen from her liberality toward her sons John & Victor, both now deceased. A large part of the real estate at Washington Heights was sold to pay debts compiled (?) by them in unsuccessful businesses. Other positions (?) were given to them on which they built and raised money by mortgages. Finally, Mrs. Audubon mortgaged her remaining property for $20,000 to enable the late John W. Audubon to prepare (?) and [illegible] of the large birds lithographer. This sum was lost by the breaking out of the present civil war, which necessarily caused a suspension of the publication under way. The interest upon the mortgages together with taxes exceeds the rents, although Mrs. Audubon vacated her own house and took board with the widow of one of her sons. For her own support, consequently Mrs. Audubon was obliged to undertake the teaching of some of the children of the vicinity, assisted by an orphan Grand daughter. This she continued until a few months since, when, at the age of 74, her strength entirely gave way – By parting with one piece of property her indebtedness has been reduced to $12,000. This amount she hopes (?) will further so reduce by the sale of these drawings, so that for the remaining years of her life she may receive a small income & be enabled to provide for the dependents (?) and her grand daughters (?)…The grand daughters of her two sons Victor G. & John W. [Maria Rebecca and Mary Eliza, eldest daughters of John W. and Victor, respectively] are now teaching in the public schools of the 12th Ward. The orphan Grand daughter [Hattie] is giving music lessons to assist in maintaining her Grandmother & self.

Lucy Audubon to Frederic De Peyster, March 20, 1863

…The Coppers I should like to sell to the mint in Philadelphia if I had anyone proper to consign them to, the Copper being such, as to purity(?), as is required for coining I am told …

Lucy Audubon to George Burgess, April 9, 1863

I this morning received a note from Mr. DePeyster which I intended sending to you, for advice as to what I should do next. I perceive from your very friendly note to me that we both take the same view of the Historical Society, and if I am well tomorrow I will write if not as soon as I can as you mention and send the letters to you, but yesterday and today I have been labouring under a bilious headache … Shall I send for the 28 Drawings and the two Portfolios from Mr. De Peyster—

Lucy Audubon to Frederic De Peyster, April 10, 1863

… It is somewhat singular that my enthusiastic husband struggled to have his labours published in his Country, and could not; and I have struggled to sell his forty years labour and cannot.

Lucy Audubon to George Burgess, April 12, 1863

Last evening Mr. Knapp [Shepherd Knapp, neighbor to the north of Audubon Park] called upon me with a message from the Gentlemen of the Historical Society begging that I would not for a short time send the Drawings to Europe as fifteen of the Committee had resolved to try and raise the money. With this report dear sir do as you always have done, the wisest and best for me only let me know when you can what that is …

Lucy Audubon to Frederic De Peyster, April 30, 1863

…To me the months that have passed away since the proposition was first made, have been painful and obliged me to submit again to the payment of an Interest that is truly throwing away my Substance under other circumstances I might now be liberated from my pecuniary embarrassment and England in possession of the Drawings.

Lucy Audubon to Frederic De Peyster, May 9, 1863

… Again I thank you for your unremitting attention to my sad affairs. I fully intended to have the pleasure of seeing you at University Place today but my cold is so bad that I have to postpone till next Tuesday my visit to the city…I caught my cold by emptying three or four boxes of Books in the Barn, but did not find a first Volume. There are several more Boxes to be looked into when I am better, and when I can hire a man to help me, but now every body appears to be moving and I could not get anyone…I am now residing in 152nd Street near the 10th Avenue…

Lucy Audubon to Frederic De Peyster, June 26, 1863

… Mr Havell’s plan for arranging the Birds I think a good one … I shall not sell them [the Coppers] for less than two thousand dollars simply because a less amount will not finish my much desired object, which is liberation from the mortgages on my former home!

Lucy Audubon to Frederic De Peyster, November 23, 1863

…I hope you will not be displeased at the sight of my handwriting again before you…the World is too busy to care for the wants or grievances of an old and lone Widow. I find it impossible to keep the rats from the boxes of the “Ornithological Biography.